By Bill Sleeman

Assistant Librarian for Technical Services and Special Collections

Supreme Court of the United States

In May of 2011, after seventeen years at the Thurgood Marshall Law Library at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, I moved to a new position as the Assistant Librarian for Technical Services and Special Collections at the Supreme Court of the United States. While I was sad to be leaving so many friends and talented colleagues at Maryland, it was not possible to pass up the opportunity to be a part of the Supreme Court. Little did I know that my first six months on the job would be such a disaster or, more accurately, a series of disasters. These incidents helped to focus my understanding of how a library disaster plays out in real time and just how very necessary a disaster response plan is. In this article, I hope to share some of this hard earned knowledge with the LLAM community while encouraging those who do not yet have a plan to prepare a disaster response plan.

Shortly after I moved to the Court, the then Court Librarian Judith Gaskell asked me to assume responsibility for preservation planning and for re-writing the library’s disaster plan. She also explained that this was not a high priority task. As I have prepared disaster plans for other institutions and have completed some preservation training from the Johns Hopkins University Library and through PALINET (now Lyrasis) I felt fairly secure in my ability to complete the task despite being new to the Court. Since it wasn’t a priority I thought I would work on it around all of the other tasks that come with learning a new position.

Unfortunately, only a couple of months into my tenure – and before the plan was started – a potential disaster loomed in the form of Hurricane Irene. By itself a glancing blow from a hurricane might not have been a cause for concern but that very week a contractor working on repairs to the Court’s roof inadvertently damaged the roof of the building directly above our rare book storage area. With help from the Special Projects Librarian, our Administrative Secretary and the Collections Management staff, we were able to scrounge up some plastic from the Marshal’s Office and were able to cover the compact shelving that housed part of our rare book collection. As a precaution we also moved our oldest and most unique material out of that area.

As we all breathed a sigh of relief that there were no leaks in the rare book area I resolved to get moving on the plan. Suddenly it seemed like a much higher priority!

I completed an initial draft of a plan and sent it up to the Court Librarian to be reviewed when we, along with much of the east coast, experienced the earthquake of 2011. While this did not cause any of our book stacks to collapse as happened at the McKeldin Library of the University of Maryland, it did send some of our books crashing to the floor so that I, along with Collections Management staff, had to spend time walking the stacks to re-shelve material and replace bookends.

Having side-stepped an earthquake, a hurricane, and a tropical storm that had passed through the Washington DC area (again, before the roof was repaired) I mentioned to a co-worker that I had better get that disaster plan approved before we had a volcano! I was starting to feel truly jinxed regarding disasters when a sprinkler head in the library’s main reading room was damaged resulting in water damage to the building and the collections. It is that event that I want to explore in more detail.

A sense of disbelief was the first reaction I had when one of my staff members stopped by my office that September morning and asked if I knew that there was water leaking in the main reading room. As I mentioned above we had been joking amongst ourselves about my recent run of disasters; it didn’t really seem possible that something else could have happened but as I stepped into the hallway I could hear the water streaming out of a broken sprinkler head.

We do not know exactly how much water was released but the type of sprinkler system installed in the Library’s reading room is intended to fully douse a fire in its particular zone or range in a few minutes – this damaged sprinkler ran for over ten minutes – and resulted in nearly three inches of water on the floor and water draining down the vertical supports of the shelving units. There was so much water in fact that it ran down between floors and was pooling also in the main hall of the Court building two floors below the library.

Despite the volume of water we were quite lucky in several ways. First, the main reading room was in the midst of a renovation project and some plywood boards had been placed across the top of the upper tier of double-book stacks which helped to deflect some of the water. Second, we had two staff members who, along with one of the contractors working on the renovation, quickly gathered some plastic sheeting from the renovation workers and then climbed up on the top level of stacks, while the water was still going, and spread the plastic out across the top of the upper shelving further deflecting the water away and protecting a significant portion of the material. Some of the contractors working on the renovation also quickly threaded plastic sheeting through the shelving in the bottom tier across the books on the top shelves.

Initial response /safety: This brings me to the first point I want to share with readers. While we are very grateful for their efforts, had I been in the room at the time I would not have allowed anyone to get up on the top tier of the bookcases while this event was going on. There was still power going to the lights and floor receptacles and the water was dousing metal framed book stacks – from a safety standpoint this was so not a good idea! One of the first things to keep in mind when responding to a disaster is that safety really does have to come first – no book collection is worth risking life or injury to protect in an ongoing disaster.

Initial response / building security: My second point goes hand-in-hand with personal safety and that is building security. As staff from around the Supreme Court converged on the area the librarians were, to some extent, relegated to the sidelines. As counter-intuitive as that may seem it really is the most appropriate course of action. Library staff were anxious to get in and start saving the materials but those several inches of water were still on the floor and the power was still on. The Marshal of the Court, the Court Police, and the Building Support Services staff really did not want or need the librarians underfoot until they had completed the tasks that they needed to do – including wetvacing up the water and getting the power turned off. The contractors working on the renovation also played a role as they quickly pitched in to help get the water cleaned up.

The key point here is that it is important for library staff to maintain contact with responders but to also stay out of the way of the public safety and facilities staff in your institution in the initial response to a disaster. Until the space where your materials are shelved can be secured it is not safe for you or your staff to try and rescue the materials

Initial response / ‘ready to rescue’: Once the power was off and most of the surface water had been mopped up – we were ready to start. Your disaster plan should guide you in making preparations for the initial survey of the damage and how you will sort and shift materials. The disaster response plan should also direct you to what supplies to have at hand for immediate reactions and what first steps you need to take. While our plan had yet to be approved by the Court Librarian I had outlined what we might need and, as building staff worked on securing the area, library staff began the process of getting organized.

Some other initial steps that should be a part of your disaster response plan:

- Contacts: Your plan should have an up-to-date contacts list. Using the list in our disaster plan I contacted a colleague at the Library of Congress as I knew that they had some cold storage space at Fort Meade. I did not yet know how much damage we had or how many books we were talking about but it is a good idea to begin making contacts and arrangements for possible responses as quickly as possible.

- Packing supplies: Your plan should outline what supplies you will need and where they will be stored. As we waited to get into the damaged area we began rounding up the various boxes, crates and book carts we would need to move and/or ship materials.

- Building resources: Your plan should outline where to get those resources you will need in an emergency but that you can’t really keep in the library. In this instance we worked with our Building Support Services to begin lining up large floor fans so that if we had to air dry material we could be ready. The fans would also be useful to circulate air in the library stacks to try and keep the humidity down.

- Staff involvement: Your plan should detail the steps that staff will employ to begin rescuing your materials. As we waited for access to the area, the Special Projects Librarian and I circulated among the library and buildings staff reminding them not to remove any books from the shelf until we could make a survey of the damage.

Once into the area we discovered that the damage was not as extensive as the amount of water suggested. The plywood and the tarps helped to divert much of the water away from the collection. However, the water that flowed to the lower parts of the building, as I mentioned earlier, traveled down the shelf support beams so that material touching the vertical supports were saturated and those next to them, books being a lot like sponges, began absorbing water from their next door neighbor on the shelf. Wet books can quickly become too heavy to support themselves and will suffer additional mechanical damage if handled incorrectly. It is a good idea to include early on in your disaster plan instructions on how to handle wet materials.

After a survey of the entire affected area, I began, with the guidance of the Court Librarian, to assign staff specific tasks to perform. One thing we needed to do very quickly to avoid the spread of water (and potential mold) was to separate the material that had not gotten wet from those that had. Even as we were working we could feel the humidity in the area going up – we needed those fans to move air and we needed to get the dry books away from the wet items. Because of the already mentioned renovation work we had several long runs of open shelves that served as swing space to temporarily move dry materials.

Ongoing action / prioritizing the response: Knowing the priorities for response is integral to planning a successful rescue. In our situation this meant being fully aware of the Court’s needs as we moved forward with salvaging the materials. Working with the Special Projects Librarian, two members of the Research Department and the Collections Management staff, we quickly determined that there was too much wet material and that it was far too compromised for us to air dry. We needed to quickly make a decision about remediation. Unfortunately we did not have any sort of “if and when” contracts in place for remediation or freezer space -“this was on my list of things to do.” The Court’s Supervisory Contracts Specialist was a tremendous help in getting an emergency contract in place with a remediation vendor. Our colleagues at the Library of Congress also kindly agreed that we could use their Fort Meade facility but since they had materials there already it would not hold very much and we would have to arrange packing and transit. After talking it over with the Court Librarian it was agreed that we needed a full service response.

As we sorted material, shifting the dry material away from the wet, the remediation vendor arrived on site. After a walk-thru of the affected book stacks with the vendor and a discussion of the Court’s schedule with the Research Department Librarians we were able to prioritize our response. It is worth noting how important it is in a disaster to involve all library staff in the rescue process. In this instance the Research Librarians had a much better understanding of the Court’s needs than I did and were instrumental in helping to identify key tools that needed to be at the forefront of our remediation efforts. Since much of the affected materials were state codes that will be retained but superseded by newer editions and state reporter volumes, we knew that we did not want to invest a lot of money in any remediation response but that the books also needed to be treated in a way that would ensure their continued viability in the future.

A final factor to consider for us was the fact that the Court’s new term was only a month away and the Research Librarians felt that we could not be without the material for long. This time frame eliminated any sort of cold remediation (freezing) treatment for the material as that would take too long for our needs; accordingly we decided to employ a combination dehumidification and desiccant air drying option. With this decision made we began creating an inventory of materials to be sent off site and packing boxes for shipment to the vendor’s treatment facility.*

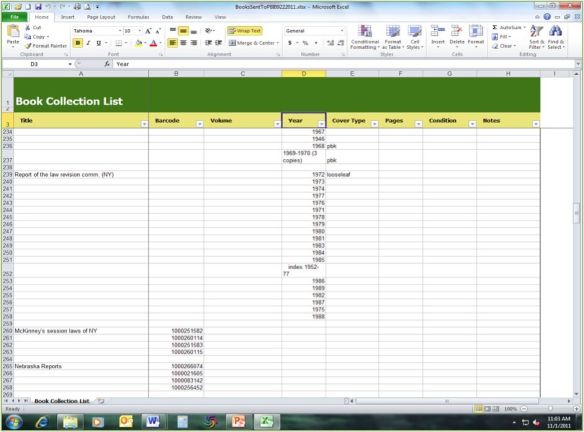

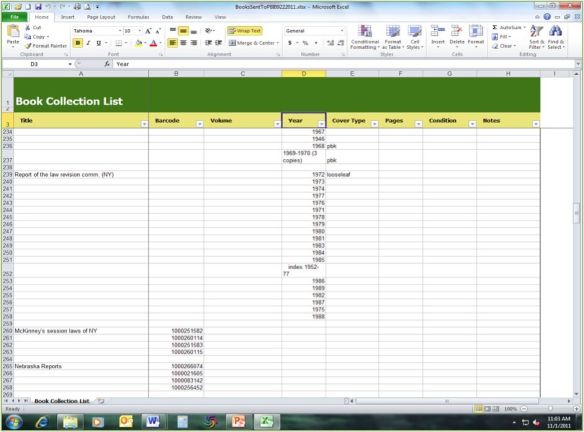

Sample inventory of material sent for remediation

Sample inventory of material sent for remediation

Post-op: On the following day, I arrived bright and early with doughnuts for everyone on staff; never underestimate the value of sugar coated fried dough as an expression of thanks for hard work and certainly everyone worked hard. I also arranged a de-briefing of participating staff from all levels of the library to evaluate what went well, what did not work and how we might need to tweak our disaster plan. When you are called to use your plan one of the best things you can do afterward is review what worked or did not and then adjust your plan accordingly.

Our books return: The books came back at the end of the second week of the Supreme Court term. Admittedly a bit crinkly but dry, mold-free and ready for use. I decided it was prudent before we sent the books to the shelves to remind library staff that we had paid for the material to be returned to a usable condition in as short a time frame as possible so while they may not look pretty they were all fully functional and stable. Using our shipping inventory (an inventory form or document should be a part of your disaster plan) we quickly re-sorted the material and got it back onto the shelves and available for use.

The role of the plan: We got through our first real disaster successfully. Our disaster response plan, although not finalized at the time of the sprinkler incident, proved to be an invaluable guide to our response. In the end we sent 530 individual volumes out for treatment. We disposed of approximately 200 volumes of various federal reporters and U.S. Reports, replacing those from back up sets that we had in off-site storage. We air dried a handful of less valuable and only slightly damp standalone supplements and directly purchased replacements for less than a dozen volumes. Staff from all areas of the library and the Court worked together as a team to deal with the event and we were able, through the efforts of so many people, to return to use the important print resources that the Court relies on and we were able, guided by our plan, to do so in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

Final thoughts

The series of disasters that represented the first few months of my new job brought home to me the importance of having a disaster plan in place and helped us to hone our response so that we can be more efficient and better prepared the next time. With luck “next time” will never come but if it does we will be ready and with a well-thought out disaster plan your library will be too.

*For more on the desiccant drying process please see the useful description of disaster response options on the Lyrasis website at: http://www.lyrasis.org/Products-and-Services/Digital-and-Preservation-Services/Resources-and-Publications/Drying-Wet-Books-and-Records.aspx (last viewed 12/30/2011)

By Mary Jo Lazun

Head of Electronic Services

Maryland State Law Library

By Mary Jo Lazun

Head of Electronic Services

Maryland State Law Library